Published on Aug. 12, 2019

Tell me MSA’s origin story. How did MSA come about?

I came to Columbia in 1970, and it wasn’t too long after that that I started getting involved with honors college stuff and those kinds of initiatives. In the early 80’s, there were some families in Springfield, Mo., down in Green county, who had heard of programs in the eastern part of the United States called Governor’s Schools: publicly funded opportunities in the summer for bright students, always with the title “Governor’s” because these weren’t part of the state’s department of education, or higher education, but part of the overall goal of the state to provide educational opportunities to bright students.

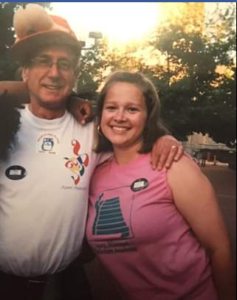

From left to right: Sam Rayburn, Ake Takahashi, Jen Meyer, John Meyer, Chris Holmes and Ted Tarkow

So these were run by governors’ offices, and some really creative and talented parents started working in 1981 or ‘82 with the Missouri legislature for something that was comparable to what had begun in North Carolina, and spread eventually west toward Kentucky and Arkansas. By 1983, they had enough swelling support in the legislature that they got approval for 1984.

The then governor of the state, John Ashcroft, vetoed the legislation. The Missouri legislature overrode his veto, and hence, our program is called the Missouri Scholars Academy, not the Missouri Governor’s school.

Whenever I speak publicly, I say MSA is Missouri’s Governor’s School, to those who know what that means. It still means something, but you have to know what it means. It’s a fully publicly funded, summer opportunity for really bright kids. The focus has changed with some of the programming; at MU, we’ve always defined MSA as being about the liberal arts. We have philosophy, chemistry, art, math, but some schools are much more focused; there’s one is Pennsylvania on agricultural sciences, and there’s one in Tennessee on international relations.

What was that first academy like?

So the first year was 1985; we had some really risk-taking people involved. We had no idea what we were doing, and no idea what to expect. This was a very new activity for MU as a whole. No one had this kind of opportunity before on this campus; the staff had very little idea what to do with teenagers, so we all had to learn, but in a nutshell, it was a smashing success. We tried to keep it spontaneous, like doing surprise night dances by the columns. In that first week, we didn’t have faculty eat with kids; we just gave them money to go eat off campus, but then the second week, we changed that.

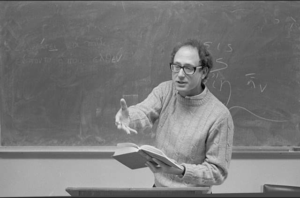

Ted wearing one of his many hats.

Since then, there have been a lot of changes: where the dorm is, certain parts of the day, some things that happen with the programming, etc. but for the most part, the academy today is no different than the first one. You take a couple bright kids, give them the chance to live with and learn from each other, go to classes, learn in and out of class, and the result is an explosion of activity internally, intellectually, and socially that stays with these students as they grow up.

Were there any emergencies during the first trial run of the academy?

We’ve never had something which we’ve not been able to handle, and that’s because of the talented people we hire. They know when to have fun, and when to exercise discipline, while being educational.

The most famous emergency was the very first night of the first year. We had a tornado drill the first night, a real tornado warning. We hadn’t had a drill yet, this was a high-stakes year, and because it was the first year, none of us knew the building. So there was that.

Another day, three kids climbed onto the dome on Jesse Hall. They had to be kicked out because it was seriously dangerous. This was also before cell phones; we had to be really concerned about alerting students and getting them to stay on MSA’s campus. We’ve always had a closed campus, so we aimed for a footprint that included the quadrangle, but the spread has gotten bigger. We didn’t get walkie talkies until very recently, but now there are cell phones, so we save a lot of walkie-talkie money.

Carving at an MSA Teacher Appreciation Dinner

What might people, even scholars, not know about MSA?

People always ask, “Why does MSA have 330 kids?” Because that’s how many students we can house in Mark Twain hall! But ironically, we didn’t use Mark Twain when MSA first started. It was a privately-owned residence hall, like Brookside now, and they would have charged a very high rate, so we couldn’t afford it. We used the Loeb cafeteria, McDavid, and the McReynolds building; it was fabulous, and right across the street from Geology. By the time MU decided to close Loeb as a dining hall, they had purchased Mark Twain, and we just moved the whole operation there.

What was that original curriculum like compared to the current curriculum?

The original curriculum–called Area 1, Area 2, and Area 3–was modeled after that of the Governor’s Schools of North Carolina, Kentucky, and Arkansas. Area 1 was what we call now academic majors, Area 2 was originally a Philosophy minor that all the scholars took. And Area 3 was and is what we called Personal and Social Development. It wasn’t too long before we found it was difficult to find people to teach philosophy the way we wanted, so we migrated Area 2, philosophy, into faculty- designed Minors. And it wasn’t too long before kids were saying, “We don’t need personal and social development, we’re very developed.” So we changed it to Personal and Social Dynamics.

Another goal we had was to give Secondary Educators (i.e. the faculty teaching at the MSA) some professional development so they could take the experience of the academy back to their home schools. That was the goal of the state in funding it, that there would be an opportunity, yes, for kids, but it would also be for teachers, so you get a positive effect across the state.

We wanted a curriculum that would get a bright student thinking about stuff that otherwise they may not think about and to do so in a social environment for group learning. So the courses have always been ones that the faculty design.

We’ve always tried to make certain that our curriculum isn’t duplicating high school efforts. If we’re doing our job right, the scholars will be thinking and learning about stuff they hadn’t had a chance to think about.

What were some early challenges in getting MSA off the ground?

Ted and Katarina Rutapina

The most important academy was the first one because we proved that we could do it. None of us had done anything like it, and before MSA, MU had never hosted so many high schoolers at one time. We met every day to figure out what we were gonna do that day, and every other academy is in some ways just a copy of that first academy, built on the knowledge we’ve learned: the spirit of the creative collegiate. the sharing of ideas, risk taking together, and getting the kids involved in planning.

I bet you that you’ll remember the dances during your academy. We didn’t know until the Wednesday of the first week that we were going to have a dance that first Saturday night, and I know that you guys now have a square dance that first friday. We didn’t have that the first year; we had it the second year because one of the teachers had known this square dance caller back at her school, who ran a square dance group. Cousin Curtis and the Cash Rebates, the original square dance caller and band, have come every year since 1986, the same group! They’re fabulous.

There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t hear from MSA alums or their parents–today I’ve heard from 5. It’s one of the great gratifying things about the program. The total number of participants is between ten and twelve thousand students, with staff it’s closer to 15,000.

What are some of the changes you’ve had to make through the academy’s history?

The stuff we’ve done, starting in that first year, is easy to replicate, but we’re looking for people every year who won’t just copy it. The organization of the day has changed a little bit by days of the week. The schedule of majors, afternoon activities, and evening activities have remained the same.

We always aim to have no more than 20 scholars in a house, and in classes, so that you don’t have classes with 50-60 students. That way each kid can come, have a really active involvement with at least 3 groups, and then have the opportunity to get to know each of them really well.

One of the other big changes that happened is that college students used to become Resident Assistants for 5, 6, 7 years; that’s really changed because now college students can and must do more things with their summers. The concepts of internships, of jobs that pay more than we can pay, the opportunities for travel, and other opportunities to use summer productively have really changed the concept of what a college student can go for, and that’s great, but in the past we would have RA’s for years. Some of my friendships with staff are going on 30 years.

One of the great things about MSA in the beginning, and I would say it should still be like this, is that I was co-director of the academy, not the director. There was someone else from the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education: Robert Parker Roach. Bob handled all the stuff with the state legislature,

student selection, some legal compliance issues, and I handled all the stuff about making it work here. This was important because it’s not a high school program or a university program. It was a partnership, and most programs have something like this: a site director and a state director. I still argue that this should not be an MU program; it should be a joint state program.

This system fell away as DESE experienced some significant budget constraints, and they bailed out around 2010. The irony is that DESE still likes to be associated with MSA, so there’s a small amount of money they contribute, but it’s a very minimal level of involvement. Back in the early days, it was 50/50; it was a model partnership between two state organizations that reflected how we should present ourselves to the public.

There are no cell phones allowed at MSA. What are your experiences dealing with technology and the academy?

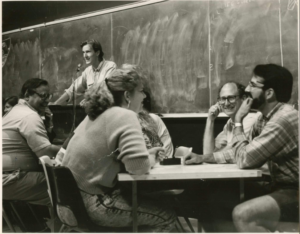

The MSA Faculty Team for the 1989 Scholar Bowl Championship: Kevin Wolf, Bill Heyde, Julia Alsobrook, Dexter Schraer, Ted Tarkow and Heather Kirkpatrick.

Technology is great, but now with the Facebook group it’s created the concept of getting ready for MSA. Obviously, we should let kids know who their roommates are, but now there are group chats, and they know each other more when they arrive than ever in the past. We know kids are gonna text on their watches and sneak their phones, but we really try to downplay it because it’s easy for kids to get so addicted to it that they don’t talk to anyone.

Because of cell phones, parents are also much more anxious if something happens. If there’s a tornado warning, they assume it’s in their child’s room, and it’s more for us to deal with. Technology has somewhat raised the hysteria level. And parents have a right to be concerned about what may happen to their kid so we have to be very sensitive to that.

Some of the mystique of MSA has also vanished because there’s so much alumni sharing; there are so many alums who want certain things to be part of the next MSA, so creating the opportunity for change is more difficult than it had been. I would argue that creating something that is never stale, without canning stuff that’s worked in the past, is a dynamic Dr. Harper and her colleagues have to be mindful of as they prepare each year.

How has state funding affected the planning of MSA?

When I was doing MSA, the academy never intended to recruit students for MU. If it did, great, but it wasn’t on purpose. I personally didn’t showcase MU except to be a nice host. But that’s one of the big changes that occurred due to funding, and MU has to market its wares now.

I’m still really active in what’s called the National Conference of Governor’s Schools. MSA isn’t unique. There are lots of programs like it; we are modeled after programs in North Carolina, Arkansas, Kentucky. We’re different from them, but we’re modeled on them. There are really great programs in Wyoming, Colorado, North Dakota, Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, West Virginia, New York, Virginia, about 25-30. I was president of the national organization for three years, and it’s still really great just to hear what they’re dealing with, how they’re being created. These are not good times for education in general and bright students in particular. State legislators want to pour money into bringing the bottom up. They’ve elected to say, “well, the bright kids can do it on their own.”

When people have upfront costs, it keeps them from applying in the first place. Even though there’s scholarship support, people don’t know if they’re gonna get it, and where that really has an impact is the variance of the population. In a typical year, we’d have better minority representation than in overall state population; these were all really terrific kids.

We now have some funds we can draw on for those who can’t afford the fee, or who can’t afford transportation to and from the academy. Another thing to consider is that a lot of kids who qualify have to have summer jobs; it’s not that they can’t afford the fee, they just need a summer salary as well, and that’s one reason public funding is essential.

Taiso is one of the academy’s most famous traditions. How did Taiso begin at MSA?

At the National Conference of Governor’s Schools, one of the Kentucky programs had a partnership with Toyota, who had a branch in Louisville, and part of the branch included outright cash for sharing Japanese culture, and at this Toyota plant they practiced Taiso. So, they performed it for the conference of governor’s schools, and I came back and I contacted Ake Takahashi, and said, “have you heard of Taiso?” and he said, “Of course.” So there it was. And we have had to negotiate where it’s scheduled some years because of construction.

You are retiring this year, right? What are your retirement plans? What will you miss most?

I’ve stepped down from the Dean’s office, but I’m still teaching next year and doing other stuff for MU. Taking a half hour or so for a conversation while I was at the Dean’s office was very very difficult, so I’ll enjoy having a chance to spend that time.